In honor of Robert Wenzel.

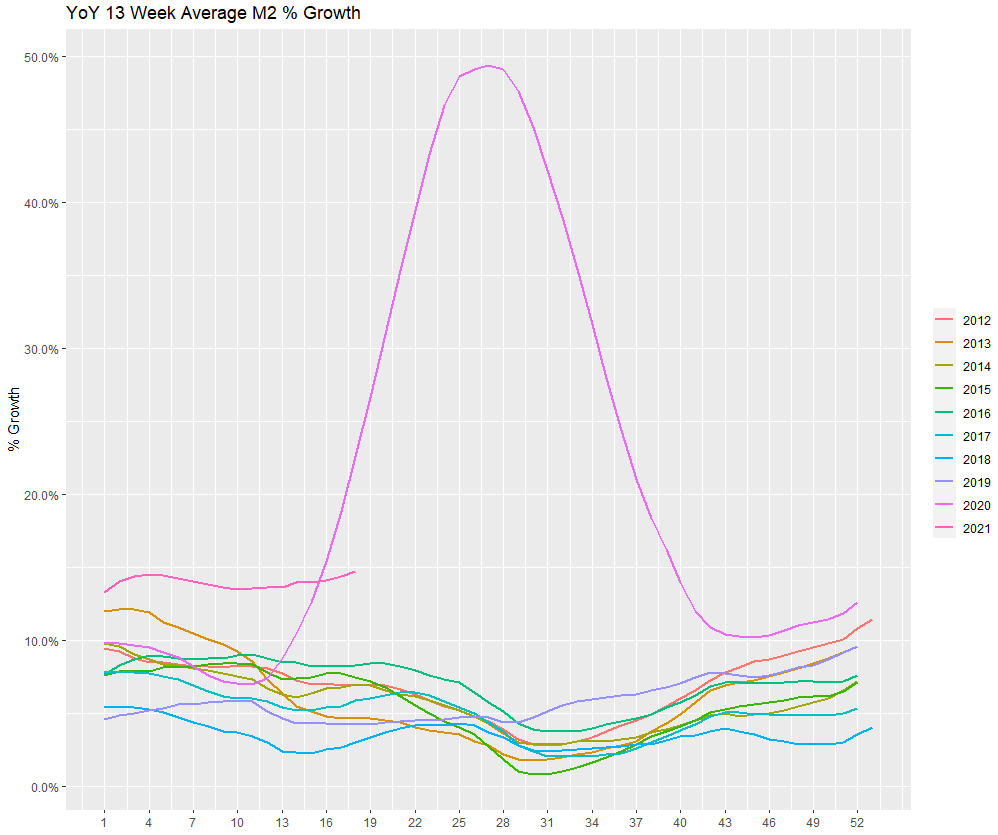

Real 6 month interest rates are negative and M2 growth is above 6%:

while Brent crude prices are trading in a narrowing range:

Will the low/negative interest rates continue to support or will growing supply pressure crude down?

I came across this FT article from several months ago which gives a good picture of where we might be headed in the oil market, as well as in other commodities. As I described a couple of posts back, the low nominal/negative real interest rates we have been experiencing have incentivized the holding of oil in storage (either in storage tanks or in the ground by not extracting) due to the negative returns available for money which would be received in exchange for the oil. It has been less expensive to keep the oil in storage than to sell it, especially if one does not have any profitable new business to invest in.

As rates have flat lined close to zero, oil prices have stayed up in the $95-$100 range since mid-2011. The forward curve, which was in contango almost continuously from October 2008 until June 2013 (front month minus third month), is now backwardated. This makes it more expensive for inventory holders to hedge as they have to sell forward to hedge the physical oil they own. Until June 2013 they were able to capture a hedge profit by selling the higher priced forward and holding it until expiration, when they could buy it back cheaper and roll their hedge forward. Couple this incentive to hold with the poor alternatives for the cash they would receive from selling their inventories, and the price support becomes obvious.

Now, however, the forward market for WTI is backwardated and inventory holders must incur a hedge cost when they sell forward at lower prices than spot. This alone should put downward pressure on spot prices as inventories are sold. Indeed, inventories at Cushing, Oklahoma continue to decline as oil is sent to the Gulf Coast for either refining or storage. If refining, this represents demand; if storage, it is just a change in location without affecting the overall level of crude inventories in the US.

But WTI prices are holding up at around $100. The normal mechanism would be for the increased supply on the market, induced by a backwardated curve, to push spot prices down until the curve structure is such that holding inventories is cheap enough to slow the selling down. This hasn’t happened yet. Is a rate rise what is needed to send prices down to a level more in keeping with what are believed to be supply/demand fundamentals?

Volatility is low across many asset classes. If volatility is a measure of uncertainty, then this is a bit strange. These seem to be some of the most confusing economic times in recent history, with ever present calls for market crashes while stock markets move up, bonds stay very high, and oil moves sideways.

Central bank policy has provided strength to most markets, as they are designed to do. This has in effect reduced downside volatility. Oil is trading at less than 20% implied volatility, well below historic levels, even as economic uncertainty is high. Oil production in the U.S. is growing and should be putting downward pressure on oil, but prices have been moving sideways since 2011. Why would $100 WTI, with rising supply and economic crashes always around the corner, be trading at <20% implied put side volatility?

At least part of the answer seems to involve central bank policy. Low interest rates have sent money out to non-traditional markets in search of yield. Commodities like oil benefit from this. Low interest rates also incentivize oil producers to keep oil in the ground. If their option is to put their proceeds from oil sales into low to negative real rate paying treasuries, then why not wait? Lastly, the money used by central banks to buy the bonds that keep interest rates low needs a home. The new money is a wealth transfer from savers to the receivers of the new money, so there is a constant flow of real, not nominal, savings to the bondholders. They will be looking for somewhere to invest the money. These three factors, put in place because of the uncertainty the world faces, have led to the paradox of lower volatility in the face of greater uncertainty.

Below is a chart showing the Goldman Sachs commodity index with real 6 month interest rates:

The mismatch between interest rates and time preferences is well known during times of central bank interest rate manipulation like we have today. But less understood is the mismatch between time preferences among developed and developing countries.

As societies become wealthier, they begin to have higher savings rates. The higher savings rates imply a lower time preference, meaning that they are willing to forgo consumption today for greater consumption later. Time preference is the basis of interest rates. Lower time preference for consumption leads to greater savings, which leads to more capital available to be lent and lower interest rates.

This all works out because a sufficient amount of capital available for, say, two year loans implies that in two years, when the project for which money is borrowed is completed and its products are being offered for sale, the buying power will be there to purchase the products. The only question is whether or not the entrepreneur calculated consumer tastes correctly.

But does this work in the world of international capital flows? Money saved in a wealthy, low time preference country that is invested in a poor, high time preference country could be at risk of a mismatch between the investment and its future products and the ability of the local citizens to purchase those products. Especially in times like these, when central banks have pushed interest rates to very low levels, and investors are searching for creative ways to earn returns, the danger of mistaking rising foreign asset prices for good investment opportunities due to time preference mismatching seems great.

Savings make capital accumulation and greater productivity possible. Increased living standards require increased productivity. From the St. Louis Fed:

Overview and Definitions

The value of the dollar should continue its directionless ways, the U.S. economy should maintain low growth, and the Fed should remain accommodative, according to the latest Wells Fargo analysis.

The U.S. current account, the difference between exports and imports of goods, services and transfers, was strengthened in the 1990s by autonomous capital inflows. Autonomous capital flows are taken in response to current prices, exchange and interest rates, and other economic factors by independent actors. These inflows strengthened the dollar. High levels of autonomous inflows seem unlikely as long as the Fed is accommodative, which it will be as long as economic growth and inflation are low.

The dollar’s depreciation was slowed in the last 10 years by accommodating inflows, which are undertaken by central banks for the purpose of settling balance of payments imbalances (the measure of currency flows out of and into a country, where positive means autonomous flows are positive) arising from autonomous flows. Accommodating inflows usually take place as U.S. Treasury securities purchases, and the sum of autonomous and accommodating flows equals zero by an accounting identity.

Three Dollar Phases

From 1995 to 2002, the trade-weighted value of the dollar rose 40%. Trade-weighting adjusts currency values based on the extent of their use in international trade. Gross capital inflows rose more than gross capital outflows as autonomous purchases of U.S. assets increased. The dollar strengthened from the demand for its use for the purchase of the assets. The increase in the financial account surplus was offset by the increase in the current account deficit.

From 2002 to 2008 the dollar declined and was volatile as the financial crisis set in, strengthening from an international flight to safety. The current account reached 6% of GDP in 2006 as high U.S. demand brought in foreign imports at same time that Western Europe and Japan decreased their imports of U.S. goods as their economies weakened. Demand for dollars fell and the currency depreciated.

Capital inflows during this period switched from the autonomous purchases of the previous period to accommodating purchases of U.S Treasury securities by foreign central banks. China in particular heavily intervened to slow the dollar’s depreciation to maintain U.S. imports of Chinese goods. Autonomous transactions decreased from 70% of gross capital inflows to 40% in 2004 (it would appear that an increase in autonomous inflows is a symptom of, and not necessarily a direct cause, of the relative attractiveness of U.S. assets and hence is not the primary cause of dollar appreciation, though it does contribute in its role in the self-perpetuating process.)

From 2009 to today the dollar has been largely directionless. The current account is back down to 2002 levels, but autonomous inflows have not picked up. Accommodating purchases by central banks are nearly double the amount of autonomous purchases of U.S. assets. As U.S. interest rates have remained low, foreign deposits in American banks have decreased. This means that foreign holders of dollars are selling dollars and buying other currencies, which weakens the dollar.

Update 7/23: Foreign investors are buying U.S. Treasuries at the slowest rate since 2006. Foreign investors, however, include U.S. hedge funds that are legally in the Caribbean. This will tend to push interest rates higher barring increased Fed purchases. This is happening at the same time that foreign central banks are decreasing their holdings and the Fed is talking about the possibility of decreasing the QE program. China, however, has increased its position by 7.8% this year. It holds $1.32 trillion. The Fed increased its holdings by 18% to $1.96 trillion.

The basic outline of Austrian macroeconomics and business cycle theory described above will now be elaborated. A three part analysis, using the loanable funds market, the production possibilities frontier, and the Hayekian triangle to model the intertemporal production structure, will be employed to this end.

Capital Based Macroeconomics

Austrian macroeconomic theory is based on the market process, as the result of individual actions, in the context of the intertemporal capital structure. Focusing on the intertemporal nature of capital allows this theory to capture the two pervasive elements in macroeconomics, time and money, where other theories can’t. In so doing, it rejects the Keynesian theoretical division between macroeconomics and the economics of growth. Mainstream macroeconomics studies economy-wide disequilibria with a focus on aggregates in a short term setting. Growth theory studies a growing capital stock and its consequences in the long term. Austrian macroeconomics, being capital based, combines the study of the short term macro, cyclical changes in the economy with the long run secular economic expansion due to a growth in capital.

This capital based approach has three integrated elements: the market for loanable funds, the production possibilities frontier, and the intertemporal structure of production, where the market process is guided by the attempted match, by entrepreneurs, between consumer preferences and production.

The Loanable Funds Market

Austrian theory defines a loanable funds market with some modifications. Consumer lending is netted out on the supply side. The supply and demand of loanable funds is broadened to include retained earnings, which are simply a fund with which a business lends to and borrows from itself. The purchase of equities, which in this context are closely related to debt instruments, is considered a form of saving.

The supply of loanable funds is defined as total income not spent on consumer goods, but instead used to earn interest or dividends. In other words, investable resources. Loanable funds are used to invest in the means of production, not in financial instruments. Demand for these funds reflects businesses’ desires to pay for inputs now in order to sell output later. Supply represents that part of income foregone by consumers for the consumption of goods now in order to save for more consumption later. The supply/demand equilibrium coordinates these actions.

The investment of loanable funds brings the loan rates and the implicit interest rates among the various stages of production in line. As more investment goes to those stages with temporarily higher returns, those stages are brought in line with the implicit rates in all other stages and the loan rate, so all rates tend to equalize. The loan rate includes the expected return. In this way it differs from the pure rate of interest, which is a reflection of societal time preferences.

Keynesian macroeconomics hints at psychological explanations for economic fluctuations. Business confidence is described as the “waxing and waning of animal spirits”. The other side of the coin from business confidence is the saver’s “liquidity preference”. Austrian theory eschews these psychological explanations and instead focuses on economics. Business confidence is assumed to be usually stable, and an economic explanation for expected losses from intertemporal discoordination is desired. For savers, the concept of liquidity preference is discarded in favor of an economic explanation of lender’s risk, which, as with business confidence, is assumed to be usually stable.

As alluded to above, mainstream macro has two conflicting theoretical constructs: one for short run equilibrium/disequilibrium and another for long run economic capital accumulation and growth. The idea of saving as not consuming is important for the short run consumption-based theory. Saving and decreased consumption are assumed to be permanent by businesses in the short run theory. The paradox of thrift enters the picture here as savings won’t be fully borrowed for investment in production due to business pessimism. For Keynesians especially, what appears to be disequilibrium is really an equilibrium with unemployment and is the normal course of things. The long run theory, however, views saving and investment as the foundations of growth.

Austrian theory falls somewhere in between these two constructions. People don’t just save; they save for the purpose of consuming more later. They accumulate purchasing power for later use. There is, of course, risk and uncertainty inherent in future demand for consumption goods. The entrepreneur takes on this risk as he tries to earn a profit from the coordination of current saving and future demand. The entrepreneur, then, is crucial in the Austrian theory.

The Production Possibilities Frontier

The Production Possibilities Frontier (PPF) can be used to show the tradeoff between consumption (C) and investment (I), rather than the tradeoff between consumption and capital goods as is normally done. This modified use of the PPF captures gross investment, including capital maintenance and capital expansion. The production of capital goods is equal to investment in any given period. A stationary economy, with no growth and no contraction, has gross investment at a level only to maintain capital.

A PPF describing a mixed economy must also capture government spending (G) and taxation (T). Conventional, Keynesian-based, macroeconomics defines total expenditure (E) as C + I + G. In the Keynesian framework, consumption is stable, investment is unstable, and government spending is a stabilizing force. Consumption depends on net income, but investment and government spending do not. Investment has a mind of its own, so to speak, so Keynesian policy calls for G to counteract changes in I to allow for stable growth.

The particular design of the tax system and the types of government spending, whether that money goes to domestic investment or foreign military activities or so forth, will affect the shape of the PPF and the specific point of the PPF an economy will find itself. Of course, governments often spend more than they bring in and finance the difference with debt. This borrowing increases the demand for loanable funds, and government deficits, Gd, are added to investment, I, on the PPF’s horizontal axis. Gd is defined as G – T.

In a private economy or an economy with G = T, the net PPF shows the sustainable combinations of C and I and assumes full resource employment. Points inside the PPF have unemployment of labor (L) and resources. This is considered the normal state of affairs in a private economy by Keynesians, where scarcity will not impede growth and C and I can move in the same direction. In fact, Keynes’ General Theory includes points inside the PPF, and the theory considers points on the PPF to represent a special case, where Classical theory describes the economy well.

Representing the Intertemporal Structure of Production

Capital-based macroeconomics can make use of the Hayekian triangle to make a simple illustration of both the value added between production stages and the time dimension of the capital structure. The horizontal leg of the triangle is production time, the vertical leg is the value of output, and the slope of the hypotenuse represents value added between stages. The simplest, point input/point output, case, such as putting a food in storage before selling the more valuable aged product, contains one stage. The triangle can be divided vertically to represent different production stages. Consumption of consumer durables can be represented by another triangle back to back with the first, where the slope of its hypotenuse represents consumption through time.

The Macroeconomics of Capital Structure

Austrian macroeconomics combines the three part analysis described above. The interest rate and the return on capital tend toward each other, so the slope of the Hayekian triangle and the interest rate normally move in the same direction in the absence of government spending and borrowing and other economic interventions. The location of the economy described by the three part analysis on the PPF gives us that economy’s “natural” rate of employment, and the clearing rate of our loanable funds market gives us the “natural” rate of interest.

The supply and demand of money is not explicitly represented in this analysis, so transaction demand and speculative demand for money are not a part of Austrian macroeconomics. The model of the economy, absent government intervention, is a system where money simply facilitates trade and is not a source of disequilibrium. As such it is “pure” theory, and not monetary theory. Finally, this method does not track the absolute price level, and instead focused on relative prices as the more important factor in the intertemporal coordination of production.

Austrian Business Cycle Theory (ABCT), on the other hand, treats money as a “loose joint”, where policy-induced money supply and interest rate changes cause economic disequilibria. As such, ABCT is a monetary theory. Keynesians consider the Real Balance Effect, where an increase in money’s purchasing power causes increased consumption, the only possible, though highly unlikely, market solution to economic depression. Austrian macroeconomics counters by using the Capital Allocation Effect, where movements in relative prices within the capital structure allow for intertemporal resource allocation and societal consumption preferences to be in line without idle labor or resources. Also unlike Keynesian macroeconomics, Austrian macro does not include “the” labor market. Instead, many labor and resource markets are represented, with labor and resources moving between different stages as needed.

Macroeconomics of Secular Growth

A static economy is easily applied using the three part analysis of the PPF, the loanable funds market, and the Hayekian triangle, but secular growth is the more general case. During growth, we have outward shifts of the PPF. At the same time, societal time preferences might not have changed, so the interest rate can remain the same, and with it the slope of the Hayekian triangle, as the supply of and demand for loans both increase. Historically, though, increases in wealth generally bring decreased time preferences, so the supply of loanable funds will outpace their demand, causing interest rates to fall. Put another way, consumption increases at a slower rate than income since saving and investment also increase with rising income.

The equation of exchange, MV = PQ, where Q = C + I, implies that the general price level declines as consumption and investment increase. Secular growth will bring lowered prices and wages in the sectors experiencing the growth with a given money supply and velocity. This growth-based deflation does not bring disequilibrium, unlike deflation caused by changes in the supply and demand for money. Growth brings greater saving and investment, which allows for a lengthening of the production structure and an eventual fall in the prices of consumer goods.

Credit Expansion and Inflation1

The money supply is unstable because governments can create fiat money at will and banks create uncovered money substitutes, meaning banks keep less than 100% reserves. Those who receive the new money first, before the PPM has adjusted to the new supply, benefit. They can trade over-valued money for goods until the new supply/demand equilibrium is reached. People living on savings or a fixed income are hurt the worst as their costs rise but their nominal wealth remains constant. Their real share of the money supply decreases.

Bank credit expansion, extending loans not backed by 100% reserves, is, like the creation of fiat money, a form of wealth redistribution. Credit expansion can have worse consequences than money creation, and the problems often appear far after the act. The benefits, however, quickly become manifest.

Inflation, including both credit expansion and fiat money creation, produce winners and losers as a new PPM equilibrium is established, depending on when each person receives the new money. Permanent winners and losers are also created by the new equilibrium. Each person has a unique spending pattern. The uneven distribution of the new money, both in space and time, will cause permanent changes in relative goods prices. This will cause permanent changes in many individuals’ consumption/investment proportions, and some will have to either buy goods which are relatively more expensive or will change their goods purchased.

Credit expansion lowers the loan rate of interest as more savings appear to be available to borrow. This would seem to reflect a lowering of societal time preferences. In fact, time preferences have not changed, and the loan rate and natural rate diverge. The inflationary credit expansion has negative consequences apart from setting off the business cycle, which will be described below. Savings, which appear to have grown, are actually hurt as savers, creditors, are repaid in devalued money. Inflation causes capital consumption as businesses believe profits have risen and under-invest in terms of the new PPM. These profits will appear to have risen most in the most capital-intensive businesses, since the greatest proportion of investment has been done under the old PPM but the profits appear in inflated money. Real profits remain unchanged, but nominal profits, appearing high, attract new investment into these sectors. Apart from investing in production above demand, investment is diverted from production which is demanded by society. This is not understood at the time, which leads to the next step in the development of the business cycle.

Saving, Investment, and Interest Rates in the Free Market

In the free market, as the investment to consumption ratio goes up due to lowered time preferences, the prices of consumer goods fall and producer goods rise. Goods of the lowest orders fall the most and those of the highest orders rise the most. The structure of production is lengthened and efficiency increases as investment flows to the higher stages of production, along with labor and non-specific factors of production. The lengthening of the production process entails more stages of production. At the same time, the price differentials between these stages narrow. A lower return per stage is earned in more stages of production. This means that the natural rate of interest decreases, and this leads to a decrease in the loan rate as well.

This increase in investment, made possible by actual lowered societal time preferences and the resultant increase in available savings on the loan market, allows for a more efficient production process. This efficiency eventually pays off in the form of more and cheaper consumer goods on the market. Everyone’s real income increases.

There is no room for a business cycle to develop in the case just described. Investment has been coordinated by capitalists and entrepreneurs with the information coming from the loan market. This is turn has been a reflection of the natural rate of interest and lowered societal time preferences. Credit expansion, while providing similar signals at first, leads to a very different scenario.

The Start of the Business Cycle

As banks extend loans not backed by reserves, the money supply increases and interest rates fall. This fall is not, however, due to a lowering of societal time preferences. Businesses borrow at the new, lower rates and buy capital goods and factors of production. These resources are put to use in the higher stages of production, narrowing the price differentials between stages. As in the first case, prices rise the most in the highest stages of production. The difference now is that the lower interest rate which has led to the increased investment has not been matched by lower time preferences and higher savings. Total money income was unchanged in the first case as the higher spending on the higher stages of production was offset by lower spending in the lower stages. Also, the lengthened production structure was offset by the narrowed price differentials between stages. Here, however, total money income increases as newly created money enters the production structure. The lengthened production structure is not accompanied by a narrowing of the price differentials between stages because spending on consumer goods has not decreased and caused a fall in the prices of lower order goods.

The receivers of the newly created money allocate their spending based on their time preferences. Businesses have over-invested in the higher stages of production and under-invested in the lower stages. They were misled by the lower interest rates. Societal time preferences and the new investments don’t match. The savings required for sustaining the new production structure are not actually there. The consumption/investment allocations of the public remain unchanged from where they were before the credit expansion, and the loan rate of interest is pulled back up toward the natural rate.

The prices of the goods used in the higher stages fall and the goods used in the lower stages rise back towards their levels seen before the credit expansion as the consumer demand for the new production structure is seen to not exist. Time preferences are actually higher than the credit expansion led borrowers to believe. The savings were never really there. The credit expansion did not increase capital investment, it simply shifted investment to a longer production structure which was not matched by societal preferences. The newly created money simply transferred purchasing power to the borrowers from everyone else. The investment was financed via wealth transfer, not real, voluntary savings.

To summarize, consumers, who eventually receive the newly created money, spend according to their time preferences, which are higher than the credit expansion loan rates would make them appear. Consumer goods prices rise as the new money is spent purchasing them, and the producer goods begin to fall as soon as there are no new loans based on credit expansion to bid them up. The old spreads between higher and lower order goods return, and the new investment is seen to be a mistake. Prices have risen for all goods as the PPM has decreased, but the relative prices return to pre-inflation levels, with some changes as described in the previous section on the PPM. Societal time preference has also been altered due to the change in the PPM, but the new equilibrium approaches the old. The business cycle elucidates the nature of the relation between the money supply and interest rates and how their manipulation affects the economy. An increase in the money supply through credit expansion cannot permanently lower interest rates; it can only do so temporarily and at the cost of economic distortion.

Some Other Effects of the Credit Expansion

The downturn and depression phase of the cycle is really the beginning of the recovery from the harm caused during the boom. Any actions that government may take to lessen the depression’s effects would only lead to its prolongation. Only further credit expansion can prolong the boom period, and the further it is prolonged, the worse its effects will be. The longer the credit expansion phase lasts, the worse the economic distortion and the resulting correction will be. Scarce resources are misdirected during the boom, and society becomes poorer, though the opposite seems true at the time.

The expanding money supply and decreasing PPM will lower the demand to hold money, and people will begin buying goods in anticipation of continued rising prices. If the dishoarded money flows to higher order goods, then profits will be lowered as the differentials between higher and lower stages become smaller. This will further lower the loan rate below the natural rate, and the correction phase will be worse.

Deflation often occurs during the correction as credit contraction sets in. This will allow for prices between goods of different orders to widen and return to levels in accordance with the natural rate of interest. But whereas during the boom phase businesses were fooled by inflation into believing their profits were higher than they actually were, the same accounting error leads them to believe that profits are lower than they really are during deflation. This will lead to more saving than would otherwise occur, which will help lessen the effects of the capital consumption that happened during the inflationary period.

1. See Chapter 12, Section 11 in Rothbard’s Man, Economy, and State.

Under the gold standard and the gold exchange standard, the possibility of redemption in gold kept exchange rates stable and foreign trade was unaffected by shifting currency values (usually brought about by devaluations). Gold or gold-backed money flowed amongst countries and kept prices and balances of payments moving towards equilibrium.

This system, from the governments’ points of view, was too restrictive, and they moved to a flexible exchange rate standard. When unemployment began to be a permanent part of the world’s economies, and the unions had gained enough political power that they could refuse a reduction in nominal wages, governments resorted to currency devaluation as a way to lower real wages and decrease unemployment. This would also cause commodity prices to rise, favor debtors at the expense of creditors, and increase exports while decreasing imports, at least until goods prices rose. Governments, however, tried to hide their true goals with talk of domestic and foreign price level equilibrium and lowering domestic costs of production (which would come about through lower real wages and decreased real business debt).

Unfortunately for the economic planners and interventionists, the effects of devaluation are only temporary, as other countries will catch on and devalue their currencies also. A race to the bottom ensues, while more devaluations become necessary since the supposedly beneficial effects to foreign trade and the balance of payments are only felt during the time between the devaluation and change in the exchange rate and the later adjustment of domestic prices and wages.

The citizens in the devaluing country are getting less and paying more in this time interval, and must restrict consumption. On the other hand, those who borrowed money for real estate or business or own stock in indebted companies benefit from the ability to pay loans in devalued currency. This of course comes at the expense of those who own bonds, insurance policies, or who hold money.

Under a gold standard, domestic money market rates are tied to international rates through redemption and the consequent stability among currencies. A flexible rate system, however, allows governments to adjust domestic rates to fit current political objectives. Interest rates are not a monetary phenomenon, they are a real economy and time preference phenomenon, and cannot be held down forever without severe distortions in the production structure, making the economy susceptible to the business cycle.

Finally, the main reason for the devaluations in the first place, the reduction of real wages, begins to be anticipated by the unions, who demand real wage increases instead. The intervention’s objectives are not met, wealth has been redistributed, and the economy is left distorted.

Credit Expansion

Fiduciary media is not the product of government, but of private banking, policy, as banks began keeping less than 100% reserves on hand and banknotes became fiduciary media. For example, checking accounts backed by less than 100% reserves will increase the money supply without the necessity of increasing base money.

Government has adopted credit expansion as its main tool for controlling the market economy. With this tool the government attempts to lessen the scarcity of capital, to lower interest rates below market levels, to finance deficit spending, and re-direct wealth to favored groups.

If interest rates are lowered without a credit expansion, a boom will not be created.

The objective of credit expansion is to benefit some groups at the expense of others. Some policies attempt to direct credit to specific groups like the producers of capital or consumer goods or to the housing sector, but all policies of credit expansion will lead to an increase in the stock market and then to an increase in investment in fixed capital through the false signals coming from the stock market.

Under the gold standard, a country that expanded credit faster than its trading partners would bring upon itself a drain of its gold stocks and its foreign reserves as holders of its currency would demand gold or stronger currencies in exchange for its over-valued money. If the government believes that this drain is the result of an unfavorable balance of payments, it might seek to limit demand for its reserves by enacting policies such as tariffs which lessen demand for imports. This will lead to a drop in exports, however, as locals use the domestic currency on domestics goods instead, causing a rise in domestic prices and a decrease in exports.

The country would then have to restrict credit in order to stop the outflow of reserves, causing a recession or depression. Businesses in other countries would defensively increase borrowing in the face of this downturn, causing their governments to restrict credit to avoid a drain of their reserves, leading to an international recession.

Under the flexible rate system, governments are able to devalue their currencies instead of restricting credit.